We are often asked for guidance on creating and maintaining inclusive, diverse, and safe workspaces for all employees. Achieving that objective is a daunting task that can be challenging to get right.

This article discusses the ability of employers to implement special programs – sometimes called affirmative action programs – to address systemic inequality, and explains why such programs are not considered discriminatory under BC’s Human Rights Code (the Code).

“Substantive” vs. “Formal” equality: The basics

As part of the broader discussion of addressing difference, significant attention has been given to the concepts of “formal” versus “substantive” equality.

Without delving into the depth of thought and scholarship behind these concepts, and at the corresponding risk of oversimplification, “formal” equality means treating people the same. In contrast, “substantive” equality recognizes that sometimes to treat people equally, we need to treat people differently.

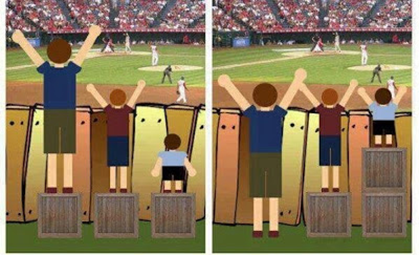

A simplistic and common illustration of the importance of substantive equality is below:

https://www.lexquest.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/fairisntequal.jpg

On the left image, everyone has been treated the same and has been given one box to stand on; this is formal equality. No one is being treated differently, but due to differences in height (i.e., a characteristic they don’t control), they cannot all see the game with the same quality (setting aside whether one wants to be able to see a baseball game all that clearly in the first place).

In the image on the right, the focus is on substantive equality, meaning the shortest individual was given two boxes, the slightly taller individual was given one, and the tallest individual was given none, which resulted in them all having the same view of the game.

This is differential treatment, but it is not discrimination, as meant under human rights legislation.

Section 42 of the Human Rights Code: Special programs

In recognition of substantive equality, Section 42 of the Code allows employees to introduce employment equity programs. Such a program will not be discriminatory, provided it:

- Has as its objective the amelioration of conditions of disadvantaged individuals or groups who are disadvantaged because of Indigenous identity, race, colour, ancestry, place of origin, physical or mental disability, sex, sexual orientation, or gender identity or expression; and

- Achieves or is reasonably likely to achieve that objective.

Employers who want to introduce special programs can apply for advance approval with the BC Human Rights Commissioner. The advantage of applying for approval is that this will confirm the special program is not considered discrimination; without approval, you may have to defend the program against a discrimination complaint on the basis that it achieves the above objectives.

More information about applying for approval for a special program can be found here. A list of special programs that have been approved in BC can be reviewed here, along with a brief description of the program, if employers are looking for inspiration.

“Reverse” discrimination: A case study

Importantly, even without approval, a program that ameliorates disadvantages will not generally be found to constitute discrimination.

A recent case illustrating this point is Miller v. Union of BC Performers, 2020 BCHRT 133 (Miller). In Miller, the complainant, Ms. Miller, identified as a cisgender and heterosexual woman and self-described herself as being bi-racial and presenting as white. Ms. Miller was a member of the Union of BC Performers (UBCP) and a writer. The UBCP had advertised a writing workshop for members that included a statement at the top reading, “preference will be given to indigenous, LGTPB+ and diverse Members.” Ms. Miller filed a complaint alleging that by expressing a preference for the listed groups, the UBCP had discriminated against her (she did not apply for the program, assuming she was not “diverse” enough).

The UBCP filed an application to dismiss the complaint, which was successful. As one significant factor, the Tribunal noted Ms. Miller had not been rejected from the workshop, so there was no evidence of adverse impact. Ms. Miller’s claim was speculative, as she self-selected out of the workshop based on her interpretation of the advertisement.

Although that was sufficient to dispose of the case, the Tribunal confirmed that “not every distinction between protected groups is discrimination,” stating “it is not discriminatory to make distinctions when their purpose, and effect, is to promote substantive quality.” For example, the Tribunal confirmed that programs that create opportunities for Indigenous people will not violate the Code, whether or not they are specifically approved under Section 42, because such efforts are a necessary part of the work to remedy the ongoing effects of colonialism and inter-generational traumas.

Ms. Miller sought judicial review of the Tribunal decision but was unsuccessful. She reiterated her view that the UBCP had been influenced by special interest groups and gave preference for opportunities in the entertainment industry to individuals who fit its conception of “diversity,” resulting in negative impacts on her acting career because she was not sufficiently diverse.

After reviewing the procedural fairness arguments raised by Ms. Miller, the judge turned to her argument that the Tribunal decision was unreasonable and concluded it was not. The judge noted that the Tribunal’s conclusion was entirely consistent with a purposive approach to the Code’s objectives and, in particular, that the Tribunal’s conclusion that dismissing the complaint summarily would further the purposes of the Code in encouraging ameliorative programs.

Conclusion: Differential treatment is not always discrimination

Employers in BC can get advance legislative protection when introducing programs to create a more equitable workplace. Even without that protection secured in advance, employers will be able to defend programs that seek to course-correct inequality and should be encouraged in that objective without fears that claims of “reverse discrimination” will be upheld.

For more information, please reach out to the author Victoria Merritt.